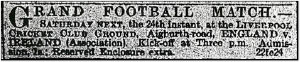

The first international football match to take place on Merseyside occurred on the 24th of February 1883 where England took on an Irish side who were making their first excursion to mainland Britain. The match was arranged under the guidance of the FA secretary Charles Alcock who decided to stage the game on the new home of Liverpool Cricket Club at Aigburth. He had attended Harrow Public School and would have been acquainted, through the “Old Boy” network, with other Old Harrovians who lived on Merseyside. One such person was Percy Bateson.

Born locally in 1862, Percy was the son of wealthy cotton broker who had, on leaving Harrow School, become acquainted with the association game while attending Edinburgh University. On returning home he played firstly for Bootle before becoming the secretary of the present day football club on its formation in 1882 which played under the name of Liverpool Ramblers. Alcock was based in London and would have certainly needed the help of Percy to observe the rules of hospitality that would have to honoured when providing for his guests. The Bateson family were members of the resident cricket club and were well connected to the local business community in Liverpool.

The Aigburth location was protected on three sides by a high brick wall and it just needed some temporary hoarding along the adjacent railway line to make the location totally secure. The playing pitch was marked out on the portion of ground farthest away from the pavilion and it was protected by a strong wire rope. The resident club, with no expense spared, had paid for their playing field to be laid out with the finest sea-washed turf and there was no better playing surface anywhere in the Kingdom. The organising committee had also arranged for the comfort of the visiting dignities the construction of a special enclosure that was situated along the side of the playing area nearest to the pavilion. Special arrangements had also been made to place the many carriages that had arrived at the location in a position that enabled the passengers to have a good view of the play while their horses, having been unharnessed, were placed at a safe distance so as to not be alarmed by the noise that was expected to be generated during the game.

The Irish party sailed, from Belfast, on the overnight ferry and arrived in Liverpool in good time for the match. A journalist from the Liverpool Courier described the scene when they took to field at Aigburth…

There was a large attendance — much larger that has properly ever been attracted to any match played in the district — whilst there was no mistaking the social status of those present. The Hibernians, arrayed in celestial blue, emerged from the pavilion; whilst at a brief interval the Englishmen, clad in spotless white, followed in their wake and as each team entered the roped off arena on the lower ground, adjoining the railway, it was greeted with loud and hearty cheers. The reserved portion of the ground was well filled, there being many ladies present; and in this section might easily have been recognised the familiar faces of no inconsiderable number of the supporters of the residence club. The opposite wing was lined with an unbroken mass of spectators from end to end, many availing themselves of a more advantageous position on the hoarding beyond.

It is clear from this account that the game had attracted spectators from all sides of the social spectrum and the attendance was estimated at being around 3,000 in number. The England side contained a blend of former public school men and working class players from the Midland region while all the Irish footballers were all based in the Province of Ulster. They were new to the association game and were beaten by 6 goals to 0.

The Irish party were later banqueted at the Bears Paw Restaurant in Liverpool before returning home on the overnight ferry. Everything had successfully gone to plan and a decent number of local football followers had been able to watch their national side in action. They would nevertheless, have to wait another six years before the FA committee would decide to stage another England game in the Mersey Seaport where the opponents once again would be from the Emerald Isle. The field of battle, however, would now be switched to the home of Everton Football Club at Anfield.

The Irish party, 15 in number, arrived in Liverpool aboard the SS Dynamic and took up temporary residence at the Shaftesbury Temperance Hotel in Mount Pleasant. They spent Friday sightseeing in Liverpool before being transported the next day out to the Sandon Hotel where the English officials, headed by Bob Lythgoe of the Liverpool FA, awaited their arrival. The party brought with them a Belfast-based journalist who gave this concise description of what the Anfield enclosure looked like in the spring of 1889.

The Everton ground, which lies in the northern suburbs of the city, is easily reached by trams and buses etc, while the accommodation for spectators and the press was of the most complete character. The unreserved or sixpenny portion of the ground is immediately behind both goals where the spectators stand upon tier after tier so no matter how crowded the ground may become, they all have an equally good view of the play. The reserve stands both run parallel down the field, the largest being covered over and extends the full length of the ground, while smaller one is specially reserved. The ground can easily hold 20,000 spectators and it may be mentioned that the teams playing here dress in the adjacent Everton committee rooms and come onto the field from an entry which prevents them from being seen until they appear in the centre of the field. The ground, which is level almost to a die, was in capital condition and about 6,000 people were present at the advertised time for the kick off. (Belfast Telegraph, 2-3-1889.)

The Kemlyn Road stand shortly after the departure of Everton

The attendance was a lot smaller than had been anticipated and this, it was reported, was due to fact that Jonny Holt of Everton, who had been expected to represent his country, had been left out in favour of Davie Weir, a player with Bolton Wanderers. The England side was considerably depleted owing to the fact that the game took place on the same day as the quarter finals of the FA Cup which were being played elsewhere in England. Charles Wreford-Brown, an Old Carthusian now studying at Oxford University, was the only amateur player in an England side that was now made up of professional players from clubs who were members of the Football League. They were captained by Jack Brodie of Wolverhampton Wanderers who, earlier in his career, had turned out for Bootle against Everton on Stanley Park. The visiting team was again made up of Ulster based players with the exception of their left back who, unlike the rest of the squad, had arrived alone in Liverpool having crossed the Irish Sea from his home town of Dublin and had reached Liverpool via Holyhead by train. His name was Manliffe F Goodbody and he was destined for a somewhat short but most eventful life.

(Goodbody was born, Dublin 1868, in to a family of landed gentry where his Father had once held the office of High Sheriff of the Kings County. He attended Trinity College and played football for his University, the Dublin FA and the Provence of Leinster. He made his International debut at Anfield and represented his country on one other occasion. Goodbody also distinguished himself on the tennis court where he reached the quarter final stage at Wimbledon and was beaten in the final of United States Championships. He became a horse trader and, while returning from France, was aboard the SS Sussex when it was hit by a German torpedo in the English Channel. The ship limped in to Folkstone but Manliffe Goodbody, killed by the blast, was listed as drowned at sea. He was 47 years old.)

Alfred Owen Davies of Barmouth FC took charge in the middle while Alan Ellerman, from the Irish FA, acted as umpire and he in turn was partnered by Robert Sloane, the Scottish born secretary of the Bootle Club. The visitors won the toss and, at 3:35, decided to play the first moiety with the slope in their favour. They surprised their eminent hosts by taking an early lead but the home side hit back strongly to win the game by 6 goals to1.

The Everton Club would not again be granted an England international until 1895 when England took on Scotland on their present home at Goodison Park. They thus became the first English club to stage an international on two different home venues while Liverpool became the first City in England to stage an international game on three separate locations. The last England international match to be staged at Goodison Park was in 1966 when the visitors were Poland. In 1973 however, due to the civil unrest at home, Northern Ireland played their two home International Championship matches at Goodison Park.