Goodison Park. Just hearing the name can make the hairs stand up on the back of your neck.

For 125 years, this patch of ground in Walton formerly known as Mere Green has been the centre of the Evertonian universe — the scene of so many of our club's triumphs and joys, its struggles and near-disasters; the place where, fittingly, its greatest-ever player took his last breath; a stage graced by some of the finest players to ever play the game, for the Toffees or otherwise; and, for the majority of its existence, a shining example to the rest of the domestic game of Everton's role as an English pioneer.

Goodison's history is as enviable for other clubs as it is a source of immeasurable pride for Everton supporters: The first purpose-built football stadium in England, the first to feature four double-decker stands on all four sides of the ground, the first to boast a three-tiered cantilever stand, and the first to install undersoil heating, the Grand Old Lady has played host to a World Cup semi-final, more international fixtures in general and more top-flight English league matches than any other in the country.

Cited by many as one of the most fearsome venues in the Premier League because of the atmosphere that can be generated by the home fans, Goodison Park has often acted as Everton's 12th man. Commentators describe how the gantry literally shakes when the stadium is at its most feverish and nothing can do the description of “Goodison under the lights” justice save for experiencing it for yourself. Magic isn't a powerful enough word for it.

And yet, while her importance to Everton has been immeasurable on those occasions when the “bear pit” has come to life, she has simultaneously become a millstone around the club's neck. Though still grand, she has aged and fallen into disrepair, an issue only now being addressed by the cosmetic improvements to the facade at the prompting of new major shareholder, Farhad Moshiri.

Tightly constrained on three sides by housing and buildings, Goodison Park has become a victim of its romantic integration with the immediate community, the viability of its expansion limited by the stadium's hemmed-in footprint and the expense of overcoming those physical boundaries.

While peer clubs have expanded their seating capacities and corporate facilities — or, like Liverpool, executed a long-term plan of buying up the houses and buildings standing in the way of their expansion — Everton have only been able to make token gestures towards the latter and failed to appreciate the need for the former when former chairman Peter Johnson sanctioned the completion of a single-tier Park End stand in 1994. That has kept Goodison's capacity hovering just above the 40,000 mark since it went all-seater in early 1990s in the wake of the Taylor Report recommendations following the Hillsborough disaster.

With roughly 4,000 obstructed-view seats, however, Goodison's effective capacity was, for many years, around 36,000; today, with Evertonians eager to watch the next promised evolution on the pitch under Ronald Koeman, the club sells out practically every home game, with thousands of those tickets hampered by pillars, overhanging tiers and “letterbox” views of the pitch. That suggests a demand for a greater capacity than the ground can currently provide and represents a frustrating cap on Everton's match-day revenue in an era when clubs like Manchester United can accommodate almost double the number of people.

Since Johnson first floated the prospect of moving the club away from Walton to a new purpose-built structure elsewhere, the “stadium issue” has vexed successive administrations and raised both dreams and horror scenarios but 20 years on, the Blues are still playing their football on Goodison Road and look likely to do so until 2020 at the earliest.

Financial Straitjacket

The saga of Everton's two-decade-long quest to resolve its growing need for a solution to the “Goodison Park question” is one largely dominated by money — principally the lack of it and, therefore, the constant search for it. It has also been characterised by a tug-of-war between arguments over the need to leave the current site and the strong desire to stay.

Peter Johnson was still enjoying the popular support that comes from appearing to be the “white knight” who rode in promising riches and investment when he proposed building a new stadium in Aintree in 1997. Having bought the club for £20m and bankrolled the acquisition of the likes of Andrei Kanchelskis, Duncan Ferguson, Gary Speed and Nick Barmby, the former Tranmere Rovers supremo had built up currency with the Toffees' faithful that he was the man to restore Everton to the glory they had enjoyed a decade earlier.

Goodison Park to me just seems to be a magical place. There was something there that made the back of my neck tingle when I ran onto the pitch for Everton, even when the place was empty.

For me it's ... the best place I've ever played football and I'll never, ever forget it.

Alex YoungThough his brochure extolling the virtues of moving was somewhat ham-fisted, and the veracity of the ballot of supporters questioned by opponents of the move like Goodison ForEver-ton (GFE), that 86% of fans were claimed to have voted in favour of a new ground came as little surprise.

By the time the proposed location had moved beyond the city limits to Cronton Colliery, however, and rumours had emerged that the Johnson regime intended on passing the costs of the development on to fans by way of massively increased ticket costs and the sale of Park Foods produce on match days, support for the project was evaporating dramatically.

And when it became abundantly clear by late 1998 with the shock sale of Duncan Ferguson to Newcastle United that incoming player transfers had been under-written not by the Chairman and the Board but by mounting club debt, the “Johnson Dome” appeared dead in the water. Johnson's right-hand man. Clifford Finch, maintained long after the duo had left the club that the new stadium was still viable right up to the time Everton were sold to Bill Kenwright's consortium at the end of 1999 but it had become a much tougher sell. With Everton having just survived a second brush with relegation, Evertonian concerns were very much on building a team capable of staying in the Premier League; plus, in the interim, organised opposition to the move in form of the GFE had mobilised.

Born perhaps of mistrust of “Agent Johnson” — the Chairman had been a Liverpool FC season ticket holder — as much as a steely resolve to keep the Toffees in their traditional home, the GFE funded a feasibility study (with the rumoured backing of Kenwright) into the redevelopment of Goodison Park by Ward McHugh Associates.

It concluded that through phased development, the stadium could affordably be rebuilt on its existing footprint with a final seating capacity of 50,000 without that number ever falling below 30,000 during the course of the project. And the study has been incorporated into subsequent analyses supporting the viability of redevelopment that have been published over the years as successive ground move proposals from the club have been floated.

The need to prove that alternative to relocation has been felt to be more acute as Everton's official position on redevelopment has hardened over time. While a renovation option was included in the Board's Kings Dock proposal in 2002, no such Plan B was offered five years later when the controversial move to Kirkby was on the table.

The stated rationale has always been primarily one of finances — chief executives Keith Wyness and Robert Elstone in turn insisted that it would be too costly to overcome the many logistical hurdles that exist at the current site. Not only that, but in the years between the advent of the proposed Kirkby scheme and the arrival onto the scene of major shareholder Farhad Moshiri in 2016, the viability of any stadium solution for Everton — be it redevelopment of relocation — was wholly dependent on enabling partners, other commercial interests, a significant naming rights deal and the proceeds from the sale of Goodison Park itself.

The planned look of Everton's ill-fated Kings Dock arena

Indeed, the collapse of the club's waterfront dream at the Kings Dock had brought into sharp focus just how difficult finding a solution to an increasingly pressing stadium issue would be. Having won preferred bidder status for an exciting multi-purpose stadium and arena on the banks of the Mersey within close proximity to the city centre, Everton needed to raise £30m for its share in the funding of the project which was to be undertaken in partnership with Liverpool City Council, English Partnerships and the Northwest Regional Development Agency.

“Small beer” relative to the huge sums of television money washing through the Premier League in more recent years, that £30m proved to be beyond Everton at the time and while a boardroom standoff was brewing between Kenwright and long-time friend and True Blue Holdings partner Paul Gregg, the estimated costs of the project began to inflate, pushing the amount the club needed to come up with even further beyond reach.

Gregg's final offer of a reverse-mortgage scheme was discounted out of hand by Kenwright and the project evaporated, the former director eventually being levered off the Board two years later, with Las Vegas leisure tycoon Robert Earl purchasing his stake in the club.

Though doubts over his role as a facilitator of a ground move persisted, along with suspicion of a shadow director in the form of long-time Kenwright associate Sir Philip Green would persist, the logic of bringing Earl into the mix seemed to crystallise with the announcement of the Destination Kirkby scheme in which Everton were to pursue a new stadium as part of a much wider retail and urban renewal project in partnership with Tesco.

Earl's experience in entertainment and hospitality — not to mention Green's background in high-street retail — seemed to be an obvious fit for a £400m scheme that promised to completely rebuild Kirkby town centre but the project never made it past the planning stage. Responding to fears from surrounding communities that the new retail development would destroy local businesses in the region, the Labour Government called the scheme in in 2009.

The public inquiry into the scheme, with the help of evidence and arguments put forth by activist group Keep Everton In Our City (KEIOC), would expose Everton's part of the scheme as having been built on sand, with a supposed £52m contribution from Tesco revealed not to be a cash infusion but simply a reflection of the expected increase in value of the site off Cherryfield Drive where the stadium was planned to be built.

Though ultimately welcomed by a significant section of the fanbase, the decision nonetheless left Everton back at square one. An alternative proposal that was floated by Bestway, whereby they would vacate the “tunnel loop” site off Scotland Road in Liverpool in exchange for land elsewhere in the city for their distribution warehouse, was discounted by the Everton board while Kirkby remained a possibility and was never revived.

A proposal pursued by local businessman John Seddon for Walton Hall Park that, by 2007, looked as though could have been pushed through to planning stage in partnership with Sainsbury's also died with Everton's decision to proceed with the Kirkby project with Tesco.

Walton Hall Park as a potential site for the club's relocation would resurface in 2012, however, when it was announced by Robert Elstone that Everton were looking at the possibility of building there in partnership with Liverpool City Council. Still in need of enabling partner, however, to share the costs of a new mixed-use development that could incorporate a new stadium, that proposal didn't get past the exploratory phase either.

Our Fortress. Our Home.

There can't be many things more integral to a football club's soul than its home ground. Football without fans is nothing but it would be considerably diminished without somewhere for those fans to call home; without a modern-day Colosseum where the devotees descend to watch their gladiators battle it out against all-comers on their own familiar patch.

The game has undergone unprecedented revolution in the past three decades but it remains, at its core, tribal and there's no question that thanks to the unique history between Everton FC and Liverpool FC, their close proximity and the fierce rivalry that has existed between the two clubs, nowhere is that more true than Blues versus Reds on Merseyside.

It's why the idea of these great institutions of English football sharing a stadium has always been anathema to both sets of supporters. Sure, viewed through the dispassionate lens of pure economics, the idea makes sense on a number of levels and did so particularly a decade ago when both clubs were planning to relocate.

At the time, Liverpool had been given permission to build a new structure on Stanley Park almost adjacent to Anfield and Everton were battling against financial logic and limited resources in pursuing the doomed Destination Kirkby project. The question of sharing a ground with the neighbours from across the Park was one regularly floated but it was met consistently with a cold reception from both sides.

At the core of the argument was always the issue of identity and for Everton in particular, going into partnership with Liverpool in this way was felt by a majority of Blues fans as though it would strike a hammer blow to their club's history as a leader, innovator and pioneer not only on Merseyside but in England as a whole.

Indeed, far from leading, there were very real and justifiable fears that no matter how equitable any eventual deal may have been, both in terms of substance and appearance, it would always seem as though Everton were the tenants in Liverpool's stadium.

Yes, compromises over things like the colour of the seats could be made and technological solutions to branding the outside of the stadium for the respective clubs on a given match day could have been found but such a shared space could never feel like home for either club.

And in a city that shares one team's name and in which the reds are already the more visible of the two clubs, it's not hard to imagine Everton simply getting lost in Liverpool FC's shadow unless they could find rapid and lasting success of their own.

Having left Anfield for pastures new, Goodison Park has been Evertonians' home for 125 years and getting into bed with the reds in an arrangement that could never be truly equal given that club's superior economic clout and global following would feel like throwing away a century and a quarter's worth of Blues heritage.

Groundsharing was always an option but only a desperate last resort that, thankfully, has never been close to becoming reality.

Staying Put

That something significant needs to be done about Goodison Park has never been in question. From the pictures of delapidated toilets in the club's 1997 brochure pitching a move to Aintree and warnings 10 years later over the very safety of the Grand Old Lady's stands to the stadium's rusting and decaying edifices and obstructed views, it's been obvious for a long while that Everton have been "kicking the can down the road" when it came to resolving a very expensive problem.

With each failed stadium move project, the debate has returned to the viability of rebuilding Goodison and, as mentioned already, there have been committed voices among the fanbase who argue persuasively that it can be done, affordably and over time with minimal disruption.

Tom Hughes, an engineer by trade, has been a leading proponent of the viability of rebuilding Goodison Park piecemeal at the existing site — either with small extensions to the current footprint or incorporating more modest upgrades centred around signficantly enlarging the Park End Stand within the current site's dimensions — and he recently published a revision to his paper, Redeveloping Goodison Ideas [

In it, he posits that the Bullens Road stand could be reprofiled to include an executive tier while the upper tier is extended upwards and that the same could be done to the Gwladys Street End. Both initiatives would require the demolition of adjacent housing and buildings, however, but would allow for new corner sections to be added to join together all four stands and further increase seating capacity.

Perspective view of a potential Bullens Road Stand with an executive deck beneath an extended upper tier and new roof (© Tom Hughes)

He suggests that the Park End would be the obvious starting point in terms of increasing capacity to compensate for a potential loss in attendance while other parts of the ground are redeveloped, either by building over the back of the existing stand or rebuilding it from scratch. The room behind the existing structure means that "a vast single-tier end stand" could be constructed along the lines of Borussia Dortmund's huge South Tribune stand, "altering the focal point of the whole stadium."

Meanwhile, Trevor Skempton, an architect who consulted on the expansion of Newcastle United's St James's Park stadium, put forth a number of solutions for redevelopment in 2007 as a response to Destination Kirkby, as well as proposing alternate sites in the city which included the north docks.

He outlined how a "minimal" redevelopment option could remove the worst of the obstructed views and increase Goodison's capacity from around 40,000 to 48,000 without the need to demolish any existing buildings. Trevor's more ambitious solutions included an "arcade option", that would incorporate the commercial structures on Goodison Road and require the demolition of 13 houses near to Bullens Road but allow for a new capacity of 52,000, all the way up to "horseshoe" and "maximum" options that, with the replacement of buildings on three sides of the existing stadium could push the capacity up to 63,000 or even 72,000.

Continuing on the theme of where there's a will, there's a way, the ambitious end of the scale would also include rotating the Goodison Park pitch to make the most of the land behind the Park End and Bullens Road or moving it towards Stanley Park and either re-routing Walton Lane or running it under a new tunnel beneath a new stand.

While technically and financially feasible over the long term many of these solutions would have required the kind of longer-term planning that was effected by Liverpool FC and their gradual acquistion of a number of houses on Kemlyn Road to make way for the recent expansion of Anfield. The process was controversial but the reds eventually got their way and were able to expand the stadium's footprint.

In order to increase the space available to expand Goodson in the near future, Everton would needed to have already implemented a strategy to buy up the commercial and residential properties on Goodison Road, Gwladys Street, Muriel Street and Diana Street while also coming to an arrangement with the Council for the relocation of the school on Bullens Road. Successive Council leaders, particularly Warren Bradley at the height of the Kirkby debate, have shown their wilingness to help in this area but if redevelopment were to be accomplished on the same three-year timescale that Moshiri apparently envisions for a new build elsewhere, most of these complexities would have to have been ironed out already.

It explains why the club have been so reluctant to entertain the prospect of staying at Goodison Park despite it being so popular with a core of the supporter base, particularly in the wake of Kirkby. If Moshiri and the Board are willing to go to the considerable effort and expense to fill in a dock, it stands to reason that the many impediments to expansion in Walton could similarly be overcome. However, a new build elsewhere provides more space, fewer complexities, less opposition from potentially hostile residents and no restrictions on the timing of construction.

It is comforting to know, however, that redevelopment on the current site is possible should all other avenues be exhausted. The idea of staying put is a romantic one, the prospect of leaving is heart-wrenching but there appears to be an acceptance among the majority that Everton have to move to progress. As long as it is to a marquee destination like the waterfront, the Blues faithful as a collective will surely be on board.

A New Hope

2016. Enter Farhad Moshiri, and suddenly, with a billionaire major shareholder on board, Everton's hopes of finally resolving their stadium issue have been given new life. With his representative, Alexander Ryazantsev on the Board, the Iranian-born businessman has quickly set about trying to move the issue forward, mindful of what he perceives as a small window of opportunity for the Blues to regain their place at the “top table” of English football.

A new ground for the club — with the attention, prestige and boosted commercial growth it offers — is seen as central to that effort and less than a year since he bought a 49.9% stake in the club, it feels as though Everton are closer than they have ever been to moving.

While the idea of redeveloping Goodison Park hasn't been discounted entirely, it is clear that the Board overwhelmingly favour relocation to one of two brownfield sites within the city boundaries — the first at Stonebridge Cross off the East Lancs Road in Croxteth, the second at Bramley-Moore Dock in Liverpool's northern docklands.

Even with all of the arguments in favour of moving laid out, the former location would be a tough sell to Evertonians. Although the often bitter divisions and debates surrounding Kirkby were muddied by its location in neighbouring Knowsley Borough, opposition to that proposal was principally founded on how far that move would have taken Everton away from not only the city centre but from the club's historical home and roots.

It's almost 12 years since we left Roker Park. To this day I've never returned to the old site. If I see it's not there then I will no longer be able to visualise it as it then was.

I must confess that visiting the Stadium of Light reminds me of when my favourite uncle went into an old folks' home. Clean, modern, and functional. Pleasant almost, were it not for the sad inevitability that you can't turn back the clock and make things the way you always knew them and wanted them to stay.

Jeremy Robson, Salut! SunderlandLeaving the city was, of course, still part of it — KEIOC does stand for "Keeping Everton In Our City" after all — but of greater concern was the club leaving behind the terraced streets of Walton for what was essentially a car park next to Tesco on a retail development on the other side of the M57. Less Emirates Stadium and more Reebok or Madjeski Stadium.

There were many Evertonians — this writer included — who felt that Destination Kirkby could eventually be the death knell for Everton as a Premier League force and while certainly not in the same league as Everton — literally and figuratively — Coventry City's dramatic decline is a cautionary tale with unsettling parallels. That club's move to the Ricoh Arena was even held up by some as a template for a successful stadium move at the time but it spelled near disaster for the Sky Blues whose future remains uncertain. It's disconcertingly highlights just how big a blessing in disguise it was that Kirkby fell through.

With Moshiri's financial backing in place, any move to Stonebridge Cross is unlikely to prove so perilous for Everton in terms of the club's survival, at least in the medium term, but there could be a serious cost to the club in terms of prestige, its heritage and the overall matchday experience if it isn't handled correctly. Certainly, the ammunition a relocation to just east of the M57 would hand Liverpool fans in their claim that “the city's all ours” would stick in the Evertonian craw; by contrast, a stunning new development on the banks of the Mersey would instantly shift the landscape of football on Merseyside in a way that was hoped for with the Kings Dock plans.

Put simply, there are huge differences between the out-of-town, drive-up business park stadium experience and the more traditional inner-city, walk-up feel that is more prevalent at Goodison Park. Transport links would obviously be improved to any new development on the East Lancs Rd, new watering holes and restaurants would spring up in the immediate vicinity, and it would be a boon to fans driving in from other parts of the country, but it would have an altogether different feel to the one that Blues and generations of fans before them grew up with and came to love in Walton.

At the end of the day, if Evertonians are going to be dragged away from their spiritual home with all its sights, sounds, smells and cherished memories then it has to be something spectacular. Nil Satis Nisi Optimum is the club's adored motto and if the resources are there, nowhere should it apply more than in a new stadium — both in terms of design and location.

This mournful reminiscence of Roker Park on the Salut! Sunderland website will ring very true for Blues fans come the day we have to leave the sacred ground in L4. If we have to leave, it has to be for somewhere so special that it eases the inevitable pain of leaving Goodison.

That's why fans looks back so forlornly at the failure of the Kings Dock, why walking past the Echo Arena that stands in its stead causes the stomach to knot a little at the thought of what might have been, and why the possibility of a twice-in-a-lifetime opportunity on the north docks is so appealing. Done right, Bramley-Moore Dock could be a golden opportunity for Everton to vault themselves back into the footballing map and transform the club's standing in the City of Liverpool.

Eight Criteria for a Good Football Stadium

- Inner-city or City Centre location. The stadium should be easily accessible by public transport. The city centre is by far the best place for this as public transport capacity drops exponentially with distance from the city centre. Matches are played at the weekends or in the evening, when there is plenty of spare parking capacity. The stadium can contribute to the overall image of the city, alongside theatres, cathedrals and civic buildings. The inner-city is the next best thing.

- Scope for Incremental Development. Football Clubs need to be able to develop continuously. The case for incremental developments is that they can change with time. A one-off completed design can quickly become an out-dated straight-jacket. But fixed historic elements can complement a changing context.

- Core Capacity of 48,000, with potential for further phases to take it, at first to more than 60,000, then — ultimately — to the appropriate size to be able to stage the Champions League Final [at least 80,000]. Supporters must be able to dream of the ultimate goal, in their home stadium, as they do in terms of their team.

- Just half the seats should be of a generous ‘premium quality'. The other half should be of a contrasting traditional ‘atmospheric quality' — that is they should be tightly-spaced and close to the pitch, ideally with an element of ‘safe standing'.

- Closeness to the action: This is of great importance in regular club football, both for the experience of the spectator, and the creation of a good atmosphere in support of the team. Distance from the pitch is every bit as important as sight-lines. That is why is notion the idea of sharing with athletics in a club ground has fallen out of favour [as against occasional big International games or Cup Finals]. Despite ingenious attempts, nobody has yet come up with a satisfactory solution.

- Eight days a week. The stadium should exert a continuous presence in the eyes of the supporters in particular and the public in general. There should be many activities every day — concerts, museum, club shop, restaurants, hotels, etc.

- Aspects of ‘atmosphere' must be given serious consideration — just as in the design of a theatre or opera house. Match atmosphere, or being a ‘fortress', has long been regarded as the accidental by-product of a cost-conscious engineering approach. But team performance, and the attractiveness of a venue to television audiences are vital factors, and both are directly related to the stadium design.

- History. Football is an emotional business — the accumulation of trophies and the accumulation of memories. Many of these emotions are bound up with the stadium, and a move puts at risk [in business terms] these ‘unique selling points'.

Trevor Skempton for KEIOC, 17th May 2016

On the Banks of the Royal Blue Mersey

If manifest destiny was contained in a chant then Everton, if they have to leave Goodison Park, are meant to end up on Liverpool's famous waterfront. There may not be much literal hanging of Kopites on the banks of the famous waterway should it come about but it would give Blues fans plenty to crow about in a city in which they have felt like a second-class citizens for too long.

As already mentioned, it's the prospect of a gleaming new stadium on the docks that makes the thought of leaving the Grand Old Lady palatable and what's most exciting of all is that not only does it appear to be the site preferred by both the Board of Directors and Liverpool City Mayor, Joe Anderson, in Farhad Moshiri the club may just have the man to finally deliver it.

Ever since first Stanley Dock and then Bramley-Moore Dock were floated as possible locations for a new Everton build, the majority of Evertonians have been envisioning their team playing them home games on the banks of the Mersey. However, in contrast to Stonebridge Cross, where the land stands ready for construction and the road links are already in place, nothing about a dockside stadium in the precise location that has been earmarked will come easily or cheap.

First and foremost, the dock itself would need to be filled in to create the nine-acre footprint for the stadium and any associated buildings, car parks and pedestrian concourses. Then there is the sheer cost of building the stadium itself which could cost upward of £300m-£400m on its own, depending on the size, specifications and materials involved.

Partial funding would come from naming rights (in the wake of the £75m USM Finch Farm deal, a £100m stadium sponsorship package for new stadium would not be unreasonable), the sale of Goodison, other sponsorship and some public money, the final amounts very much dependent on whether the stadium forms part of Liverpool's bid for the 2026 Commonwealth Games.

Then there are the transport links and infrastructure upgrades that would be required, although Mayor Anderson has already greased the wheels there with his new Ten Streets scheme which proposes a new creative quarter in Liverpool linked to the city centre by new roads, a railway station on the line to Sandhills station, pedestrian and cycle thoroughfares. The improvements would not only benefit any new Everton stadium on the docks, they would serve the area earmarked for Peel Group's planned £5.5bn Liverpool Waters development that promises to extend the transformation and regeneration of the waterfront from Prince's Dock north to Wellington Dock.

A development by Everton could, in concert with the Ten Streets proposal, kick-start the renewal of the area and shape the rest of Peel's plans which have yet to be fully realised. Negotiations with Peel over Bramley-Moore Dock are still in progress but the club are hopeful of a positive outcome and a possible announcement before the end of the current season.

Once filled, the site itself affords the club and its developers much more space than the current footprint at Goodison Park and provides scope for future expansion and room for leisure, entertainment and dining establishments as well as a much desired museum where the Everton Collection could finally find a permanent home.

Goodison Park and the Park End Directors' car park fit comfortably within the area earmarked for potential development at Bramley-Moore Dock once it has been filled in.

Recreating the ‘Bear Pit'

Perhaps more than any stadium of its size and ilk still standing in England today, Goodison Park is an encapsulation of the magic and the history of the English game. It can also be one of the loudest, most raucous, spine-tingling and inhospitable footballing arenas in the game.

And therein lies perhaps the greatest fear for Evertonians when it comes to the issue of what to do about the Grand Old Lady. Because, whether it's piecemeal redevelopment, complete reconstruction on the current site or relocation elsewhere, preserving what makes Goodison such a feared venue for opposition teams on the one hands and such a beloved fortress for Blues fans on the other is arguably the single most important aspect of any new stadium. Its very success could depend on getting that part of it right and ensuring that the new structure eventually feels like home.

Encouragingly, the experience of other clubs of Everton's size, standing and history have overall been positive and bode well for the Blues if they can pull off something grandiose at Bramley-Moore Dock. While acknowledging the obvious need to allow time for “the new ground to breathe” and feel familiar, fans of Arsenal and Manchester City, for example — two clubs who left their traditional homes for modern facilities — appear to have settled into their new environs well despite the wrench of leaving their previous grounds.

It helps that in either case there doesn't appear to have been organised opposition to relocation. Both sets of supporters largely accepted that moving was an inevitable step for their clubs — for the Gunners, it was necessary to keep up with with the clubs who have become their peers during the Premier League era; for City, the offer of the City of Manchester Stadium was simply too good to turn down.

As Lee Hurley of Arsenal fan site The Daily Cannon says:

I think, for the most part, most accepted that this was what was needed to keep Arsenal moving forward.

Don't forget, we were also on the crest of a wave when the decision was made, winning league titles and the build started just a few months before we completed an unbeaten season. That sort of form on the pitch buys the management unlimited space to do what they tell fans is best for the club.

Plus, it meant more people could get a season ticket, it was a five minute walk from Highbury and there was no need to go play games in Milton Keynes for a season!

Meanwhile, Alex Timperley of the Typical City blog explains:

Honestly, I don't think there was any serious opposition. City were in dire financial straits and a new stadium at an affordable cost was a God-send.

The new stadium was cited as a major reason that Abu Dhabi piled in with all their money a few years later, so it seems pretty obvious that the move was value for money.

Looking back, it's hard to see why fans would have fought the move. There was real love for Maine Road but it wasn't fit for purpose by the time of the move.

Creating the conditions for Goodison's “12th man” and that “bear pit” atmosphere that has become its hallmark when the supporters are up for it will be a fundamental question facing the architects who would be charged with the undertaking.

It's no trivial matter. From European nights like Bayern Munich and Fiorentina on the one hand to those relegation-defying games against Wimbledon and Coventry in the 1990s and home derbies like the 1978 and 2004 editions, the atmosphere that can be generated at Goodison has been one of Everton's greatest assets over the years. Certainly, it's hard to quantify in terms of results the power that the Gwladys Street appears to sometimes have to almost suck the ball into the net while the cacophony that can be generated four stands in aggregate makes for an awesome experience and a significant advantage for the Blues at home.

Encouragingly, Dan Meis, the US-based architect whose firm has been given the brief to design Everton's new stadium has been active on Twitter in recent months, engaging with fans and offering occasional thoughts on how certain concerns can be mitigated by modern design and technology.

Chief among them is the need for intimacy in any new structure and the proximity of the fans to the pitch. Uefa regulations on the minimum distance between the stands and the edge of the playing field will likely make replicating the pitch perimeter at Goodison impossible but ensuring that they are as close as can possibly be allowed should be priority number one.

After that, it's hoped that steeply-banked stands to generate the feeling of the home support being on top of the opposition are part of the design brief. Where the new Wembley Stadium and Arsenal's Emirates Stadium, with their shallow gradients sloping away from the action lack that intimacy, Juventus Stadium in Turin — in terms of the interior, at least — has been held up by many as the gold standard for what Everton should be trying to achieve.

With its tight dimensions — the stands are just seven yards from the pitch — and steeply raked seating, it provides close to optimum conditions for trapping the sound generated by supporters and creating a cauldron of noise to intimidate opposition teams. From a supporter's point of view, that sensation of almost being on top of the pitch reinforces the connection and engagement with the match itself as opposed to a more detached feeling of being a mere spectator.

While not much to look at from the outside, with its steeply-raked stands and their proximity to the pitch, Juventus Stadium has been held up as the example for Everton to follow when it comes to preserving that unique Goodison atmosphere at a new ground. (image via needitaly.com)

Then there are positive moves that Everton can make in terms of seat allocation, provisions for singing sections, keeping existing season ticket holders together and the designation of a “home end”, something that was largely missing at the Emirates Stadium when Arsenal moved in. This is touched on by Lee of The Daily Cannon who admits that his club's new stadium is a far cry from the very Goodison-like Highbury in terms of atmosphere:

It's hard to say that the Emirates has even come close to the atmosphere at Highbury apart from for massive games and there are a few reasons for that. When allocating the new seats to season ticket holders, groups were split up, they didn't think to include a 'singing section' or a 'home end' or anything like that.

With a larger capacity stadium you also get more football tourists who alter the atmosphere as well and it has been said that watching a game at Arsenal can sometimes be like going to the theatre - you can be expected (by some) to sit, watch, and be quiet.

Architecturally, the Emirates is a magnificent stadium.

When it first opened, it was just bare concrete walls — a totally soulless place - but they've spent the 7+ years undertaking an 'Arsenalisation' of the stadium.

That's the thing, these things take time. I'm sure when the club first moved to Highbury somebody thought it was worse than Plumstead Common and it took time for it to feel like 'home.'

While the Etihad Stadium has also been criticised for a lack of atmosphere, an issue that some City fans ascribe to attempts by their club to artificially generate it, nowhere has the debate over the damaging effects of a stadium move been more heated than West Ham United's new London Stadium. The Hammers' controversial move away from Upton Park to the former Olympic Stadium was trumpeted by their board as a signal that the club was poised to join the Premier League's elite.

Season ticket demand for the 60,000-seater stadium was strong but the pitfalls of leaving an atmospheric, old-fashioned four-stand ground for the vast expanses of a converted athletics stadium have been laid bare as West Ham struggle to feel at home in their new surroundings. Jokes about the distance between the stands and the pitch have become commonplace among away supporters and the whole situation stands as stark a warning as there could possibly be for Everton as they plan their own potential relocation

The different atmosphere is a mix of everything. The stadium isn't really optimised for it — stewards are constantly telling everyone to sit down, there's the lingering suspicion that the club doesn't care about us as much anymore, etc.

City fans are quite hard to impress as it is; we're a pretty cynical bunch. Throw in the commands from on high for us to make more noise so it looks good on telly and it's no real surprise that many fans don't feel very cooperative about it all.

The bottom line is the same for almost all Premier League clubs: If they want better atmosphere then they should make football affordable for all, especially younger people. I would imagine that applies to Everton as well.

Alex Timperley, Typical City on the Etihad Stadium

It's why talk of Everton's proposed move to Bramley-Moore dock being part of Liverpool's bid for the 2026 Commonwealth Games makes Evertonians so nervous. Indeed, the words “running track” are enough to strike fear into the hearts of any Blue but where there is a will, there is a technological way to accommodate athletics in the structure, even if it will add complexity and expense as a result. And by incorporating a docks stadium into the city's 2026 bid, it would be incumbent on the council to come up with a greater contribution to the costs of the scheme, thereby lessening the burden on Everton.

Quite how easily a retractable seating component could be accommodated in a stadium with steep stands would be a question for the architects but Singapore Sports Hub's solution offers a template — albeit in a more bowl-like structure — by which Everton's new ground could make room for a running track or even additional concert seating as needed.

Video: Retractable seating at the Singapore Sports Hub

It's worth noting that the City of Manchester stadium was constructed with it eventually becoming a full-time football ground in mind which helped City mitigate many of the problems that have befallen West Ham. As Alex of Typical City describes, with planning and fore-thought, it is possible to accommodate both athletics and football if both purposes are part of the original brief.

City clearly did a better job than West Ham ever will and we actually paid for a lot more of it ourselves, which is nice.

For a start, the deal for City to take over the ground was signed in 1997 — five years before the Commonwealth Games it was built for. Plans to convert the stadium from an athletics one to a pure football one were built into the purpose and design behind it all so there weren't any real concerns we would be stranded half a mile from the pitch in the way West Ham fans are currently not enjoying.

Missing the Kippax is one thing, but this wasn't a slapdash job and the conversion came in many times cheaper than the cost of converting the Olympic Stadium. It also came with scope to expand the stadium in the future, works which the club have subsequently undertaken.

Other impediments to an optimal atmosphere include corporate hospitality, something that will be vital to the financial success of the new ground and Everton's commercial performance in the years to come. Goodison Park has a comparatively small allocation of such facilities and this is expected to be rectified at the new structure, wherever that ends up being.

Here again, Juventus's stadium sets the example, with a single row of executive boxes tucked under the upper tier so that, in contrast to corporate spectators taking up — or, alternatively, leaving empty — blocks or bands of open-air seating, the disruption to the body of home support is minimised as much as possible.

Then there is the not insignificant question of initial capacity and its effects on atmosphere weighed against future growth — or, Heaven forbid, decline. While Goodison routinely sells out at the moment and you would imagine that in a ground free of obstructed views, better catering and facilities and a team challenging for Champions League football demand could be much higher, there is little appeal in a 60,000-seater stadium that is only two-thirds full.

While Juventus Stadium has a relatively small capacity of just over 41,000, it's not unreasonable to expect that Everton could build a similarly intimate stadium by adding just 10,000 more seats while retaining the potential for future expansion beyond that if needed, thereby preserving the matchday atmosphere.

Safe to Stand Again

If there's one ingredient that could help hugely in fostering a vibrant atmosphere inside the new ground it might just be the installation of so-called “safe standing” sections. Nowhere does the spectre of the Hillsborough disaster hang heavier than on Merseyside and it's that tragedt's closeness to home which explains why Bill Kenwright has, until very recently, dismissed the prospect of reintroducing standing to Everton's stadium out of hand.

The emotional rejection of the notion is understandable. 28 years on, the disaster that befell Liverpool FC is still tangible given how long the search for justice for the 96 who lost their lives on the Leppings Lane terraces has gone on. Only now are the families and friends of those affected able to feel any sort of closure from the tragedy.

Technology, like time, has moved on in the interim, however, and it's important to explain that the safe standing sections being implemented in previously all-seater stadia today have very little in common with the old fashioned terracing that used to dominate the grounds of Britain's football clubs prior to the post-Hillsborough Justice Taylor recommendations.

Safe standing rail seats in Hanover, © Stadionwelt.de

Indeed, these new enclosures are much more like rows of seating than the expanses of concrete steps and intermittent crush barriers of old and are safer for spectators than the current all-seater stands where away fans in particular will often remain on their feet throughout the match anyway. Many Evertonians can recount stories of those “limbs” moments where wild goal celebrations have sent them toppling through rows of seats, often resulting in injury!

Each safe standing row can have seats built in should they be needed — regardless, they mark a reserved seat number to control numbers in each section — but when not in use are bolted back seamlessly into a continuous barrier that impedes the kind of swaying and fluidity of crowd movement that was prevalent on old-style terracing and which contributed so directly to the crush at the front of the Leppings Lane end at Hillsborough. What's more, if the volume of supporters in each enclosure is a concern, these sections can be designed to be as small as you like, thereby reducing the risk of overcrowding from those fans who would defy their seat allocation in order to stand with their mates.

It's an option seriously worthy of consideration whether Everton move or stay put and as more and more clubs build such sections into their own stadia — as Daniel Taylor describes in The Guardian, “Germany has led the way and, one by one, the other leagues are following behind. Austria, Switzerland, Hungary, Belgium, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands all now operate safe standing.” It's pleasing, therefore, that the Blues' CEO Elstone recently announced that the club would enter into consultation with supporters over the issue of safe standing and whether it was something they would like to see introduced.

Waterfront Dream or Concrete Desert? A Tale of Two Franchises

Bastions of the past like Goodison Park still exist today in the unlikeliest of places, not least in the United States, the land of rapacious renewal and corporatisation — albeit in its most traditional and nostalgic sport. Boston's Fenway Park and Chicago's Wrigley Field — the former still boasting wooden seats; both still featuring sight-lines blocked by supporting pillars — stand as monuments to the early days of baseball and the inherent romanticism of “America's past-time”. The American Football teams of the NFL, meanwhile, appear to be locked in an arms race over which team can build the most expensive, technologically advanced stadium in the country.

Teams in both sports — and its true of NBA basketball and NHL ice hockey as well — can be transient to a degree that is utterly alien to English football fans though. Far from being clubs and organisations inextricably and desirously rooted in their local communities, these “franchises” can uproot and move across an entire Continent seemingly at the drop of a hat in search of new “markets“ and commercial opportunities.

Both of California's most celebrated baseball teams, the San Francisco Giants and Los Angeles Dodgers, for instance, were founded in New York — in 1883, in the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn respectively — but upped sticks and moved to America's opposite coast in the 1950s to “new frontier” markets. Both were almost as old as any football club from England's Football League but they were able to sever ties with the communities in which they first grew with an ease that is virtually unthinkable in the English game. (MK Dons' move out of London to Milton Keynes is the only modern-day equivalent in England but it was bitterly fought and hugely resented by fans of the old Wimbledon FC.)

That speaks, perhaps, to the wildly different sporting cultures in the respective countries, ones born of very different national experiences and geography. The feelings of and opposition from — to the extent that there are any — the fans that these franchises leave behind have little bearing on the decision and that is particularly and obviously true in the cases where the moves are ones predicated on the very need for survival.

As it relates to Everton's stadium situation, the Giants' recent history, together with that of the city's nominal NFL team, provide interesting parallels, one that would only reinforce the attraction of a waterfront home for the Blues as opposed to an out-of-town development.

Having been compelled to head west from their original Harlem locale in 1958 by the need to leave the crumbling facilities at the Polo Grounds, the Giants were twice almost forced out of San Francisco before they found a solution to remain in the city.

Attempts to construct their own purpose-built alternative to playing baseball in the 49ers' often windy and frigid concrete bowl at Candlestick Point were stymied by local opposition but the team was saved from the prospect of relocating to Toronto, Canada in 1976 and St. Petersburg, Florida in 1992 when new ownership stepped in vowing to keep the team in the Bay Area.

It wasn't until 2000, however, that a resolution to their long-standing stadium saga was found when they moved into a brand-new venue right on the water on the south end of San Francisco's downtown area. The Giants have since flourished in their retro-design, 43,000-capacity home — with its red-brick facades, dockside promenades, gaudy Coca-Cola bottle slide and giant baseball mitt, it is simultaneously quaint and intimate while also being unashamedly corporate — and have had sold out attendances for years. (Coincidentally, of course, they hosted Everton's International Champions Cup match against Juventus in 2013.)

Success on the field has brought further wealth for the club off it — they won the World Series three times in five seasons between 2010 and 2014 — and the presence of AT&T Park led to rapid urban renewal and development of the surrounding area. Served by a new tram link and a pre-existing rail terminal just steps from the stadium's entrance, the immediate vicinity saw shops, restaurants, bars and high-rise flats spring up at dizzying speeds, the process accelerated and spread further by the influx of “tech” money in recent years that has made San Francisco one of the most expensive real estate markets in the world.

AT&T Park, the San Francisco Giants' 43,000-seater purpose-built waterfront baseball stadium where Everton played Juventus in 2013.

Faced not so much with an imperative but desire to move rather than rebuild, the 49ers defied both the wishes of its fans and the efforts of the city's Mayor to keep the team in San Francisco by eventually opting for a move 45 miles south to the city of Santa Clara, adjacent to San Jose. Perhaps because of the perceived futility in battling it or that accepted American tradition of teams migrating across the country, opposition from supporters groups was virtually non-existent. Not like the fight put up by KEOIC, of course, when faced with the prospect of Everton moving the comparatively short distance of 5½ miles down the road when Destination Kirkby was on the table.

That's not to say the move wasn't unpopular. The 49ers unquestionably lost an element of their jilted hardcore fans, either angered by the fact that the franchise left the city bearing its name to move so far away or simply priced out of following their team by astronomical season-ticket prices and one-off down-payments just to be eligible to buy one. But in a market of almost 8 million people, the owners no doubt felt it would be easy to replace old fans with new to fill a 68,500-seat stadium.

In contrast to the Giants who almost won the World Series two years after moving, the 49ers — coincidentally enough, like Everton they haven't won anything since 1995 — have hit bottom since leaving Candlestick Park. The team that Jim Harbaugh led to the 2013 Super Bowl quickly disintegrated and the franchise is going through a horrible downturn, a situation that, perhaps combined with disillusioned fans, has led to paltry attendances at their massive $1bn Levis Stadium.

More than other sports, the NFL, with its equality-driven draft selection process that gives the worst performing teams each season first crack at hiring the best young players every year, is cyclical and the 49ers' time will surely come around again in the next few years. In the meantime, the owners' attempts to avoid television camera shots of vast banks of empty red seats is a visual reminder of a stadium move that has yet to bear fruit — many of them will already be accounted for by season tickets sales but there will be no parking, food, beverage or merchandise sales on game days to fans who don't show up.

Clearly, American and English sports are so culturally, structurally, economically, and geographically different that it would be unwise to draw too many comparisons between them. Given the sheer size of the markets in which most US teams operate and their commercial pulling power, they appear able to build new stadiums almost at will, although many of these costs are passed on to the paying customer in the form of increased ticket and concession prices in a way that Everton simply could not.

Nevertheless, the example of the Giants is a shining one, particularly in view of Everton's preference for a new stadium at Bramley-Moore Dock, of the benefits of staying close to the centre of the city, building a new structure of which supporters could be proud, acting as the catalyst to the renewal of the surrounding area, and reaping sporting success at the same time.

Image is Everything

There is so much to be inferred about a club's stature and prestige by the size and aesthetics of their home stadium and it's for that reason that Evertonians are awaiting so eagerly the first renderings of what the majority hope will be a stadium on Liverpool's famed waterfront.

It will be no easy brief for Meis architects whose head, Dan Meis, has promised that the Toffees' new ground will look like none other. Everton fans have massive expectations, a keen sense of their club's long and proud history, and will demand a design befitting the motto Nil Satis Nisi Optimum.

That was clearly evident when the first artist's impressions of the proposed Kirkby stadium were released to a decidedly lukewarm reception. While the “Johnson dome” drawings, with the blue roof, red brick facade and Prince Rupert towers, were a significant nod to Everton's history and the futuristic arena at the Kings Dock were suggestive of a forward-looking club, the Destination Kirby renderings suffered from an apparent lack of imagination.

The club supposedly drew inspiration from FC Köln's stadium, which had been one of the chosen venues for the 2006 World Cup in Germany but, no doubt because of budgetary constraints, the final designs looked more like replicas of Millwall's New Den or Southampton's new ground at St Mary's. The “cow shed in Kirkby”, as the proposed ground came to be known by its most vociferous opponents, suffered further by its proximity to a planned Tesco supermarket, with fans ultimately feeling that the whole notion felt decidedly “un-Everton”.

None of the subsequent alternatives to Kirkby ever got as far as the planning and design phase — not officially anyway; a design accredited to IDOM (below) for a potential build on Walton Hall Park exists on the Internet — so the renderings that many hope will be unveiled this year will be the first time Evertonians have seen a new vision from the club of what an alternative to Goodison might look like.

Purported artist's impressions of a Walton Hall Park stadium by IMOD (via Skyscraper City)

Design, like art, is supremely subjective, so it will be impossible to please everybody but if the vision is grand enough, it's safe to say that the majority of supporters will be on board. The location at Bramley-Moore Dock, if that is to be the site ultimately selected, brings with it some particular choices though, given the current aesthetics of what is a historic docks district on the one hand — high walls, concrete drum towers at the entrances and the Grade II listed Victoria Tower that overlooks Collingwood Dock — and the architectural mix that Peel envision for the rest of the surrounding docklands area on the other.

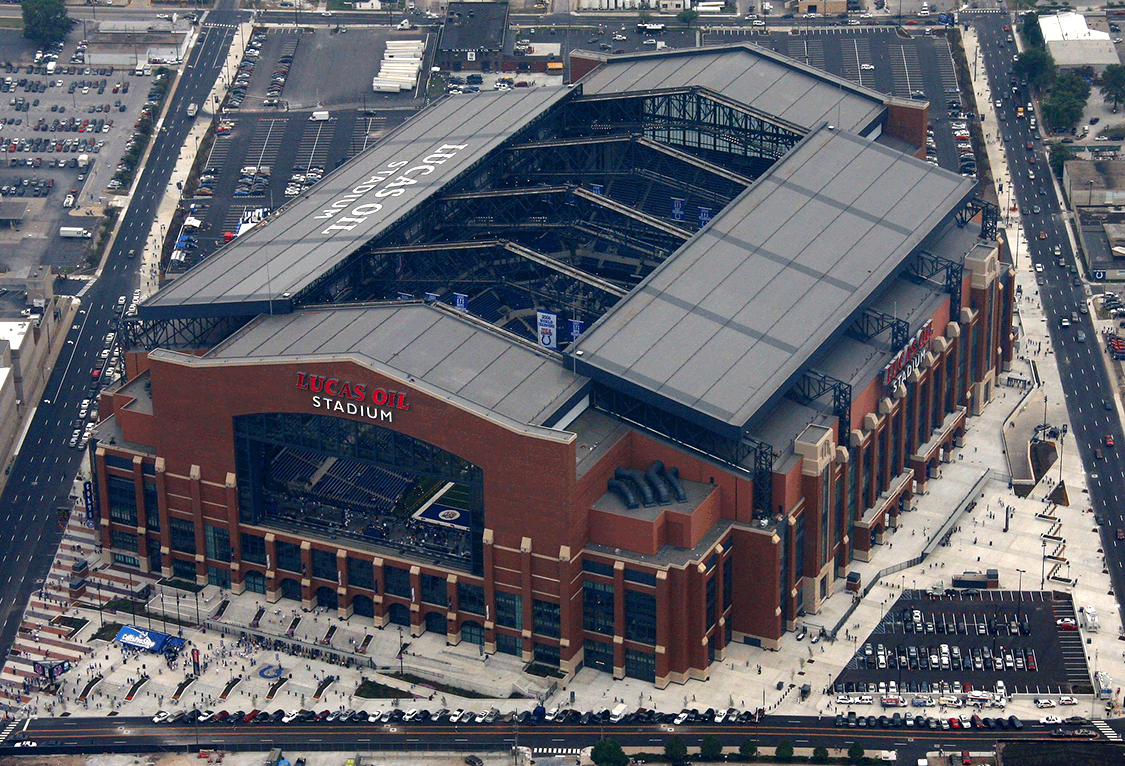

In the case of the former look, Lucas Oil Stadium, home of the NFL's Indianapolis Colts, has been put forward as a possible model for Everton's new build. It's boxy, retro-styled design is evocative in some respects of Ibrox Park and other English grounds with commanding red brick entrances and one that would not look out of place on the north docks.

© Lucas Oil Stadium, home of the Indianapolis Colts

In terms of a more modern vision, there are myriad possibilities, from a mostly glass structure like the supposed Walton Hall Park design above or mixture of steel and glass like Tottenham's new development to a bright, open structure like Meis's Stadio della Roma or Feyenoord's planned development on the banks of the Maas river.

Feyenoord City (top), the 63,000-seat stadium planned by Ronald Koeman's former club, and Athletic Bilbao's San Mames Stadium (bottom) provide glimpses of what a waterside stadium for Everton might look like.

What is critical is that the stadium be instantly recognisable as Everton's from both the exterior and interior and in keeping with what would be a highly-prized and visible location in the city, particularly from the air. A unique design with iconic elements that separate the structure visually from rival grounds when seen from the outside is a must which is why Meis's engagement with supporters on social media in this regard have been so encouraging.

Likewise, the inside of the stadium should say “Everton” as much as Goodison Park currently does. St Luke's church won't be coming with us and the imposing pillared structure of the Main Stand will be replaced by something else but replicating the look of the Archibald Leitch criss-cross and vertical steel balustrades that are so unmistakable on the front of the Bullens Road and Gwladys Street stands will hopefully be central the new design.

If We Must Away...

While these options remain just proposals, Evertonians who have endured one failed ground-move project after another are, understandably, remaining cautious over the deliverability of either Stonebridge Cross or Bramley-Moore Dock.

If there is a sense that there will only be so many opportunities for Everton to rejoin the elite clubs of English football, it's one that Farhad Moshiri at least seems to feel and that has been reflected in the speed with which he has consolidated the Blues' long-term debts, made funds available for transfers and set the wheels in motion to resolve a two-decade-long stadium issue that has dogged successive regimes.

At no time since Peter Johnson first raised the idea of leaving Walton has a new Everton stadium felt more possible and while leaving Goodison Park will be heart-breaking, the chance to progress that is on offerby the water on the north docks is not one that should be turned down. And it has to be the docks. The argument that once you get inside the ground, it shouldn't make much difference where it's situated is prima facie a rational one, but when it comes to matters of the heart and the raw emotion of football, there's so much more to it.

The build-up and pre-match rituals in the streets and pubs around the ground; the walk-up; the walk out; the sense of place within the city and the community of which Everton FC has been a fabric since 1878... all of that contributes to the matchday feeling and the subsequent mood and atmosphere within the stadium for the game itself. It's hard to imagine preserving or fostering that on the outskirts of town in Croxteth.

Bramley-Moore Dock might only bring the Blues a half mile or so closer to the city centre but if the Council's aspirations for Ten Streets bears fruit, there will be a tangible extension of Liverpool right along Regent Road to the gates of a new Everton stadium, with all the eateries, pubs and hostelries that would surely follow to transform the area and allow a new matchday experience to flourish.

Should Everton get the green light to proceed with Bramley-Moore Dock, all of the collective focus of the Board and supporters must then be on ensuring that the new development is optimised as much as possible towards retaining the uniquely "Everton" aspects of Goodison, with football first and foremost in mind, and providing the best conditions possible for retaining the unique atmosphere that Evertonians can generate in our existing home.

Sunderland legend, Jimmy Montgomery, recently recalled the “Roker Roar” for which that club's former ground of 99 years was nationally famous, describing it in terms of the team starting with a goal's advantage; such was the power of the wall of noise that could created within those four stands. But for Rokerites turned Black Cats, that signature of their football club was lost in the move to the Stadium of Light.

Where we love is home. Home that our feet may leave, but not our hearts.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.It is absolutely imperative that Everton don't make the same mistake; that the "new Goodison" be designed in such a way as to keep Everton's passionate fans as close to the pitch as possible no matter where they are seated and to maximise their collective voice. Steep stands, an intimate environment, perhaps limited safe-standing enclosures and meticulously planned layout vis-a-vis standard, season-ticket, premium, executive and corporate seating would all contribute towards creating the ideal environment.

Accommodating a 2026 Commonwealth Games bid won't sit easily with many supporters simply because of the potential compromises that might have to made with respect to the final design of the stadium, although nothing should be discounted until an architect can fully explain what's possible, particularly if the contribution to funding model is what makes a dockside move possible.

The possibilities on offer on the waterfront are exciting, however, and they could form a metaphorical cornerstone on the foundations of Everton's re-emergence as a major power in the English game. The location, as part of a major regeneration project on Liverpool's north docks in concert with Peel's development and the Council's own plans, has the potential to put the club front and centre again in the city, enhancing the brand and the attraction to the world's players, managers and investors.

It's a dream and a vision of a big future. Can we make it happen? Hopefully it won't be too long before we find out...