Real Footballers' Wives — Marina Kay

Sheffield was one of Hitler's main targets during the war because of its steel industry and I can still remember the sky being completely lit up by the air raids during the blitz. My dad was called up in 1940 when I was four, and my brother Geoff was only a two-year old toddler.

Our street in Southy Green eventually got hit so we had to go and stay with my grandparents at the Sheffield United side of town. Mum's role in the war effort was to work as a tram conductor so Geoff and I went everywhere together and would play in the streets with our friends until it went dark. I never left the house without him, he was great company; he was thoughtful and more reserved than me and our childhood was full of laughter.

I loved my nan and grandad to bits; he was an old rascal and worked as a bookie's runner. Bookmaking was illegal then and I remember him standing me on the street corner and telling me to keep an eye out while he took bets. When my mum found out she wasn't too pleased.

I was eight years old when a man wearing an army uniform knocked at the door. I went and told my mum there was a soldier outside looking for her. She came out of the kitchen and as soon as I saw her face, I realised it was my dad. Straight away I could see why she'd fallen in love with him. He was so handsome; he had black hair, big blue eyes and the most beautiful smile.

Our bombed-out house was rebuilt when the war ended and the four of us went back to live there, and that was where I stayed until I got married. If I'd stayed with my grandparents, I probably wouldn't have met Tony because he was from the Sheffield Wednesday side of town.

I adored my dad and we grew very close but he'd contracted tuberculosis in the Far East and became ill almost as soon as he got home. He was in and out of hospital most of the time so we never went anywhere with him because he was too sick, but I would sit with him for hours and hours talking and getting to know him. Sometimes he could hardly breathe and would just sit in his chair and then he'd be back in hospital again. I didn't have him for long, the one time he went in he caught pneumonia and he was too weak to fight it. He was 32 when I lost him and I'd only known him for six years.

Tony lived at the bottom of the hill in Southy Green and I lived at the top. We went to Shirecliffe to play their school at netball once and he stopped to watch the game but he was with his pals and they were all jeering and wolf-whistling and trying to put us off. He had the reddest hair I'd ever seen.

My best friend, Marge, was in the Woodcraft Folk and she knew Tony from there. Woodcraft was a bit like Boy Scouts but without the discipline, they would go tracking animals, studying nature and learning about the countryside. Tony loves that sort of thing and he loves to be out in the fresh air. Marge introduced us when I was 15; I'd finished school by then and was at commercial college learning shorthand and typing. Tony was a plasterer working on a slum-clearance housing project they were building called the Manor Estate. He'd been an electrician before that but he got the push for acting daft. I liked him and he made me laugh.

We started courting and would go out with a crowd of friends from school to the dance at the City Hall or to Glossop Road baths. On a Saturday night, they would cover the swimming pool with boards and it became a dance floor; it was a bit springy but it did the trick. Everyone was jiving and rock 'n' rolling to Bill Haley and I loved it. Tony didn't like rock ‘n' roll much so I'd dance with somebody else and save the waltzes, foxtrots and quicksteps for him. The Big Band sound was his kind of music and he would whirl me around the bouncy dance floor.

I didn't know anything about football and I still don't, really. Tony was quite happy with that; his dad was the one who followed Sheffield Wednesday. My mum remarried a few years after my dad died; Peter was an upholsterer and joiner by trade and he wasn't into football either; he liked motorcars and motorbikes. I didn't get on with him at first and I resented him but as the years went by we got on a bit better.

Tony signed full-time as a professional for Sheffield Wednesday when he was 17 but he only started to play regularly in the first team about four years later. He didn't have a car until after we married so in our free time we'd get the bus to Nottingham or Derbyshire and go and have a look around. We tried to get out of town if we could and would wander off into the countryside, just two of us.

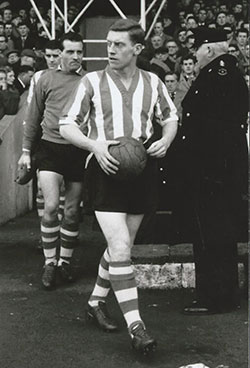

Tony as captain of Sheffield Wednesday

He had a suit and I had a dress made in matching fabric, it was dark blue check and we thought we were the bees-knees. We had a fantastic time in our teens but we used to argue. His parents and mine were friends and they used to go to the same social club, so they'd know when we'd fallen out and would engineer ways we could bump into each other. Eventually he'd come round to our house and my mum would shout ‘Stanley Matthews is here', and we'd get back together again.

There were no restaurants or places for teenagers to go to in Sheffield and everything used to close at 10 O' clock, so now and again a group of us would book a coach to take us over to Manchester or Nottingham for a night out or else we'd shoot over to Derbyshire, which was only 15 minutes away and everything stayed open 'til 11.

Marge met Jim, her future husband, when she was 17 and they're still together and happy to this day. Once she got married she didn't really come out with the group any more. We had some other friends called John and Nina Wragg; she was a very excitable Italian and started to teach me to drive in her Triumph Herald. I enjoyed it and got right up to taking my test, but when we moved to Liverpool, the traffic was a lot heavier and faster so I never carried it on.

Geoff went to do his national service in the army and was posted to Aden in southern Yemen. Tony went into the RAF because he was promised a local posting so he could continue to play football at the weekends. Initially he did his square-bashing at Padgate in Warrington and was supposed to be there for six weeks, but he broke a bone in his foot playing for Sheffield Wednesday reserves and was sent to the casualty wing with his leg in plaster. He decided he'd recover more quickly in the comfort of his own home, so he picked up his wages, altered his sick note from three days to eight and headed back to Sheffield. Unfortunately, Wednesday sent a telegram requesting the RAF release him for a game and that was when they realised he wasn't there. When he got back they put him in the jail for three weeks for going AWOL.

He was more mischievous than bad and he never got into serious trouble; he just got bored really easily. Another time they charged him with ‘dumb insolence' and made him peel a mountain of spuds as his punishment for giving the drill instructor one of his withering looks.

Life went on and while he was in the RAF, I was working as a secretary at an advertising agency and still going out dancing at the weekends with my friends. We would write to each other two or three times a week and he would send me pictures of my heartthrobs, Burt Lancaster and Rory Calhoun, which he'd cut out of magazines to keep me going 'til he got home at the weekends. We had gold bracelets made, mine said ‘Tony and Marina' and his said ‘Marina and Tony', and I wore mine all the time. I missed him madly while he was away, but I didn't tell him.

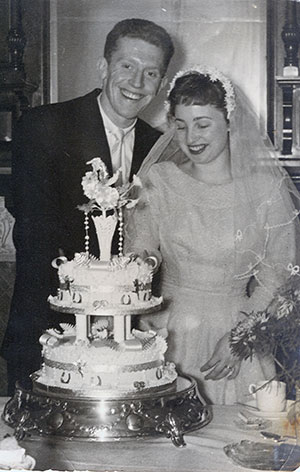

We got engaged on my 21st birthday and the only advice I got was from the local landlord, Ted Catlin who was also the Sheffield Wednesday scout and he told us we weren't allowed to sleep together the night before a game. Tony is 10 months younger than me so he had to get permission from his parents, but we married in St Cecilia's church at Parsons Cross in Sheffield on 28 September 1957. He had a match in the afternoon so we had to have our wedding at 10.30 in the morning. The following day he went to Doncaster with Peter Swan - I suppose that was my honeymoon.

We moved in with Tony's parents, Jenny and Mac. Tony was always away and I was pregnant so it was just perfect and it meant that I wasn't on my own. I couldn't have wished for better in-laws; Jenny was a great ally and we got along famously, she was the only person who called him Anthony and he was the apple of her eye. Mac was wonderful too, warm, clever, funny and gifted with a beautiful voice; he was always bursting into song. Him and Tony would have contests and try to out-sing each other.

Nobody was more dedicated to football than Tony. We always say that when he pops his clogs, we'll put his ashes in a leather case-ball and kick him about. His first love was actually rugby but he wasn't tall enough, he was great at cricket too; in fact he was selected for trials for Yorkshire and I've washed enough of those whites to last me a lifetime. He was as fit as a fiddle; he used to race the bus up the hill while he was holding his breath and he trained hard all the time. Somebody told him to mix sherry with a raw egg and it was supposed to give you a big boost of energy. It sounds ridiculous but he swore by it and drank it before a game. He said they gave it to greyhounds and it worked well enough for them.

Ricky was born in March 1958, two weeks overdue. Jenny was cooking the tea when I got the first twinges; she went to phone an ambulance but I refused to go until I'd eaten. It was just as well because I had a long night ahead of me and ended up having a caesarean. The only thing I can really remember is the ambulance with bells ringing and flashing lights, but he was born beautiful and perfectly healthy.

Albert Quixall was a Wednesday player and the first footballer to take ballet lessons. His wife had a dancing school and he used to do the publicity shots with her. He was transferred to Manchester United when they tried to rebuild the team after the Munich air disaster, so after Ricky was born we moved into his old club house.

Tony went into business with Peter, my stepdad, and they called themselves Burniston and Kay Property Developers. One time he'd been up a ladder fixing a sign and Eric Taylor, the Wednesday manager, had driven past and seen him. He'd already told him off about having a kick about in the park with the local lads but to see him dangling off a ladder was too much. He reminded him that he was a valuable player and wasn't insured to do any dangerous jobs, so he had to take a back seat in the business. Peter took over the day-to-day running of it and Tony would lend a hand when he could. The business did quite well and he carried it on when we moved to Liverpool.

We had to move to a bigger house when I fell pregnant again, so we bought Jimmy McAnearney's place. Russell was born in April 1960 and before I had time to turn round my little girl, Toni was born in July 1961. Tony came to the hospital with a suitcase full of little dresses demanding to see his daughter. All the boys were born bald but she had a real thatch of red hair, it was like a comedy wig, some two-year-olds don't have as much hair as Toni did.

She could be a bit volatile at times; we used to say that when that midwife smacked her, she didn't shut up for 13 years. They say women are supposed to bloom in pregnancy but I looked bloody awful. I felt fine but I was really pasty faced and people were always asking me if I was ill. That bloom just wasn't there and my hair was terrible, but my kids were all beautiful.

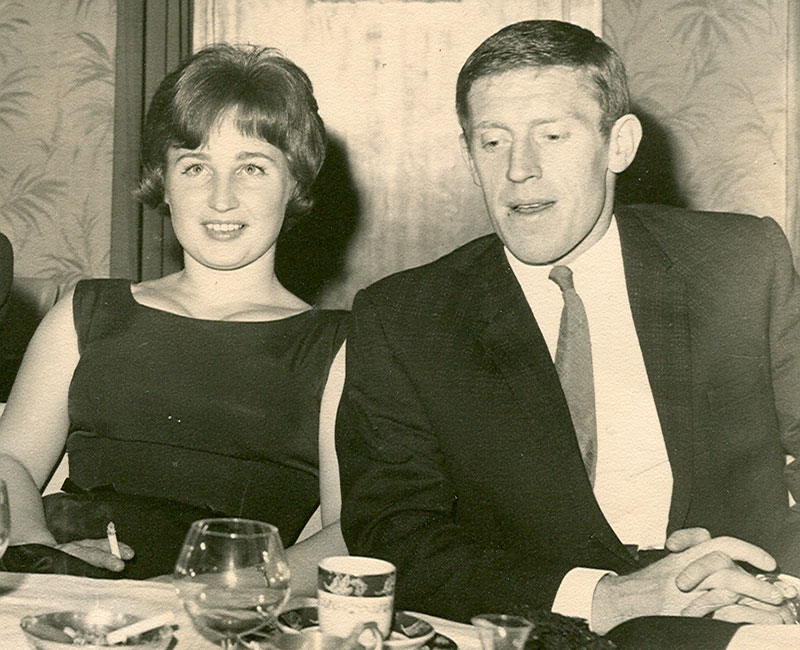

Marina and Tony Kay in 1962

I never thought we would leave Sheffield, in fact it was only days before that I'd been talking to some of the Wednesday wives, I said we would be there for life. A week later Tony was transferred to Everton and had to go straight away. Yet again I was pregnant and I decided not to move until after the baby was born, but I knew I would be going eventually. I wasn't scared of going because I knew Tony would be there, but I was scared of leaving my friends and family. I'd never been away from Sheffield apart from on holiday, so it was quite daunting. Jenny was the most brilliant mother-in-law you could hope for. She was a big help with the children and we were great friends who had many a good laugh. I knew how badly I was going to miss her.

When Everton won the League in 1963 the players and their wives were invited to Torremolinos but I was heavily pregnant, so I couldn't travel. The club gave me a beautiful cocktail watch instead; I still have it and it's engraved on the back with 1962-63 Champions'.

Jamie was born in May 1963, the day before Tony made his England debut in Switzerland. He scored a goal from the halfway line that day; I saw it on the television and almost burst with pride. I got a dozen red roses from Frank Clough, a journalist on the Daily Mirror; I was 26 and had four kids all under five. My dancing days were over and I felt like I'd been washing nappies forever.

Before I went over to Liverpool, and to make up for missing Torremolinos, Tony said I could go away on holiday and that Jenny and my mum would look after the kids between them. I went to Majorca with my sister in law, Joyce, and we had a fabulous time.

Joyce is five years older than Tony and she absolutely idolised him. She had the same red hair and a fantastic sense of humour and worked in the Batchelors food factory. Some days she'd bring home Victoria plums the size of coconuts. Her uniform was a green overall and a white turban, she looked quite exotic and one year she won the Miss Batchelors beauty pageant. As Tony and I started courting, she married Dennis and moved round the corner and called her first daughter Denise Marina, after me. We're still very close to this day and she's still great company.

I needed to get somebody to help me with the kids because Jenny wasn't there anymore, so we got a woman in and I decided I would go back to work part-time as a shorthand typist at a local agency, just for a week out of every month. I loved it, it kept my hand in and got me out of the house and into adult company for a few hours, but then the papers got hold of it and printed a headline ‘£100-a-week wife wants a job'. I only worked two or three hours at a stretch but they thought it was outrageous because Tony was the record signing in the country and was earning £60 a game. The big money caused a huge sensation at the time, but they seemed to have forgotten the players had been on strike a couple of years earlier when they were only earning 30 bob a week for entertaining tens of thousands of people.

Everton's chairman, John Moores sent a chauffeur-driven car to take us to Liverpool when Jamie was about four months old. The first house they showed us was in Aintree and it was lovely, but it wasn't big enough for the six of us so they offered us another in Kendal Drive, Maghull and that was perfect because it had an extension over the garage. Part could be used as a playroom and part as a bedroom, and that was where we settled.

I met some great people in Maghull and I loved living there. The club was good to us, too; they would send us groceries every week and it was nice to be remembered. When you move to another city you have to start all over again. I got to know my neighbours, who were very kind to us, but it was so lonely when the kids had gone to bed and the house was really empty and quiet.

Jenny used to come to Liverpool a lot; she'd phone from the bus station and say she was on her way or she'd ring my mum and the two of them would come over in her car and stay for a few days. We were great friends and it made it much easier to cope with things.

Tony and I still argued from time to time and one night I threw all his clothes out of the window. When I woke up there was a white rabbit in the bathroom which he'd found in somebody's garden on his way home from a nightclub. He often used to bring it home with him after that.

My closest friends were Norma Vernon and Gordon Brown's wife Brenda. Gordon was what they called a spiv; a wheeler and dealer and a mad Evertonian and he took a real shine to Tony. The Browns helped us a lot; they were older than us and took us under their wing. Gordon died a few years ago, I couldn't get to the funeral but Tony did and I sent a wreath from us all.

Most of the players lived in Maghull and a bunch of us used to meet up every now and again. Jeannie Parker, Alec's wife, Pat Gabriel, Norma Vernon and Rowdy Ron Yeats' wife, Margaret but we all had young children so we didn't get together that often.

It was quite a lonely life because the men were always away. Christmas was the worst because there were lots of games, they still had to train every day and they couldn't eat too much or drink. In the summer you wanted to go away with your kids but the men would be on tour or at a training camp somewhere, so holiday time was always a bit lonely, too. If we could find a baby-sitter, I'd go out to special occasions but I didn't go to the match unless it was a big game, because he didn't really like me to watch him play.

The thing that wound me up about being a footballer's wife was if I went out for an evening with Tony - and those evenings were so few and far between - and people would come and pester. It got right on my nerves. If they just came over and to say hello or asked for an autograph then that was fine, but they would pull up a chair and want to discuss the match in detail, and I knew that would be it for the rest of the night. Then there would be the women coming over and trying to edge me out of the conversation. I've known girls come and stand right in front of me with their back to my face. It's annoying and you can't really do anything, although I lost my temper on a couple of occasions. Once I remember was after a party and we were getting in the car to go home. This woman came up screaming at me for some reason or another and stuck her hand through the window and tried pull my hair - so I wound the window up and trapped her in it.

The night before the story broke we were in the Royal Tiger in Liverpool. Gordon Brown had got the nod from somebody at the Sunday People that they would be running the story the next day and it was as if the bottom had fallen out of the world. We were trying to avoid the reporters, but they were everywhere so we darted off in the car but there was a crossed wire somewhere in the dashboard and every time we turned a corner, the horn blew. We were trying to get away but telling them where to look at the same time. We didn't stand a chance.

As if it wasn't bad enough, the story was reported wrongly. The headline was ‘Football's Shame' and it said Tony had thrown a match against Ipswich, when in fact, he'd been voted man of the match that day. His crime was to bet against his team, which was more stupid than sinister but it had happened so long ago, he'd forgotten about it by then. Literally overnight my life changed and became a waking nightmare, it was terrible and it kept getting worse. One minute I had people to talk to and the next they were avoiding me. I don't think it was because they all necessarily believed what they were hearing; more that they were embarrassed and just didn't know what to say. I've had a few arguments about it over the years, I can tell you that much.

Jimmy Tarbuck rang and invited me and the kids to go and watch him in pantomime with Frankie Vaughan. They sent a car for us and off we went. The kids were thrilled to bits and they went backstage afterwards and met the cast. I was so grateful.

I never thought Tony would go to prison, but I think he knew. The trial was at the Nottingham Assizes and on the last day, I was at home with the kids. I asked if he was taking the car and he said he would leave it behind. I knew then that he wasn't coming back

It was an open prison called Thorp Arch in Weatherby near Leeds. Gordon Brown used to drive me there to visit. Peter Swan and Bronco Layne were in there too. There was a photo in the Liverpool Echo of me standing at the gates with Tony's football boots. Les Edwards was the reporter who wrote about the case the most. I've never seen that picture since; they were supposed to send me a copy but with the move back to Sheffield and everything, I never got to see it.

The prison governor was very kind; he rang me a few times to say Tony was depressed and sad, and he let me talk to him. His job was to make camouflage nets for the armed forces, but the nylon made his eyes really sore and he was put on gardening duties instead. I think he quite liked it because he was outside in the fresh air. One time I visited and they didn't know where he was, but they found him eventually in the middle of a field. He wasn't trying to escape or anything, he was just meandering.

He didn't look well, so I decided to cook him a steak and take it with me next time. I wanted to keep it warm so I rolled it up and put it in a thermos flask but when I got there we couldn't get it out again. We didn't know whether to laugh or cry.

Everton were all right with me. They said we could buy the house, which we started to do, and then they backed off and kept their distance. They weren't nasty or anything like that, but they stopped sending the weekly groceries.

Tony, Peter and Bronco were sentenced for four months and when they were due for release there were dozens and dozens of reporters hanging around outside the gates and right around the prison walls. The governor had been in the Army so he came up with a tactical escape plan. He decided they would be let out in the middle of the night and they were smuggled out over some sports fields at the back of the prison and bundled into cars. Peter Swan and Bronco Layne went off towards Sheffield and we never saw them again and we sped away to Liverpool with Gordon at the wheel. We cuddled each other all the way home; I couldn't let go of him.

He'd started a waste-paper business before he got sent to prison and I kept that on until he came back. I didn't drive so I hired a man and I gave him a percentage of whatever he brought in, he didn't get a wage. Tony took it over again when he came out, but the football wasn't there and he couldn't handle it. He still went training every day but the trouble was that the day the ban came he went on to ‘self destruct', he pushed the button and he wouldn't let go. He couldn't handle the concept of living without football, it was more than he could bear and he started drinking a lot. He just couldn't cope with the void in his life. Nobody loved football more than Tony and I honestly believe that.

Jenny was diagnosed with cancer and I went back to Sheffield to see what was going on and she died while I was there, I had to tell Tony and I didn't know what to say because he loved his mum more than anyone else in the world.

He'd been to see her with the rest of his family the night before when she'd come out of the operating theatre. She said she was feeling fine so they all went their separate ways home. For some reason, Tony went back alone and asked if she was really feeling OK. She told him everything was fine and there was no more pain and died shortly after he left. She was 52 when we buried her and she'd died in the hospital she'd been working at for years.

Mac went to pieces. He'd been a bit of a lad in his day and had won a bare-knuckle boxing match to win the money to buy her wedding ring. He loved her to bits and his heart was broken. He recovered eventually and years later he remarried, but it was never the same. His new wife was OK. She looked after him and they had each other for company but her and Tony didn't see eye to eye and it was a mutual dislike. As soon as Mac died she went off to live with her family in America.

Tony pictured with his children

Tony left England for Spain in 1967. I was still living in Maghull and I put my secretarial skills to use and went to work for an agency but I had to try and fit it in around school hours. I tried to keep the house on. They turned the gas off, they turned the electricity off but it was when they started digging up the drive to cut off the water I realised I would have to surrender. I left Maghull in 1969 and went back to Sheffield; Geoff drove over and picked us up. We always joked that we went there by chauffeur-driven car and came back in rent-a-van with four kids, two goldfish in a bowl on my knee, a pregnant cat, no job and no home but as they say in Yorkshire “Ne'er mind eh? Summat'll turn up”

My Mum had settled in the same area as my grandmother, the Sheffield United side of town so that was where we went, too. I got a bit of flak, but nothing I couldn't cope with. There was a bit of name-calling and people talking in stage whispers and one fella used to stand at the back of me singing made-up songs - one day I'd had enough, so I rounded on him and gave him a crack.

Geoff moved over to Spain in 1985. He bought a steak bar in Nerja near Malaga and soon settled into the way of life. He sold it a few years later and invested in a beach bar. It suited him down to the ground. He became known as Geoff the Beach and that was where he stayed until he became ill in 1996. He had tests but nobody seemed to know what was wrong so I told him to come home and we'd get him checked out properly. He was diagnosed with cancer and died in Sheffield in 1997; it was the most awful shock.

The only time I really resented Tony was when Russell came home one day sobbing. I asked what was wrong and he told me his friend had gone to town with his dad but he couldn't go because he didn't have a dad. It was times like that I hated him. I took all the kids over to Spain to see him a couple of times but my middle two are so fair skinned and they just couldn't handle the heat. We could never have settled there.

None of my sons play football; they played at school but not to any great standards. Imagine having Tony Kay as your dad — he was a hard act to follow. Ashley, one of my grandsons, is a really good footballer but I don't think he's interested in following it as a career. His brother Gavin played ice hockey for the Northern Counties but he prefers roller hockey now, he's good at that too.

I never felt as if I made any sacrifices for Tony because we were teenagers together and we'd done most of the stuff we wanted to do by the time the children came. We had a great time, it was fantastic, but I'm glad I'm not a footballer's wife now. I don't envy them at all; they've got nothing I want. I'm quite happy being a mother, a nan and a great grandma. I'm not answerable to anybody, I can do whatever I please and I don't have to compromise or fight anybody for the TV's remote control because it's mine. No shirts, no cricket whites or stinking socks, no lying awake at night waiting to hear the car pull up and wondering where he's been.

We're still in touch and I see him from time to time and we all think the world of him. He's a legend around these parts. People still talk about Tony Kay in Sheffield he was the local hero.

Tony Kay played his last match as a professional against Wolves on 11 April 1964.

In April 1965, along with former team-mates David ‘Bronco' Layne and Peter Swan, he was found guilty on charges of ‘conspiracy to defraud' for his part in a betting scandal while he was with Sheffield Wednesday.

All three men were jailed for four months, fined £150 and banned from football for life. It was the most publicised match-fixing controversy in the history of English football.

Marina passed away on August 15th 2009 — Tony was at her bedside.

Taken from Real Footballers' Wives — the First Ladies of Everton, still available for purchase in book or Kindle form or from Becky Tallentire directly. You can contact Becky via @Bluestocking63 on Twitter or via email