Every once in a while, I post photos on Twitter from my painstakingly-curated Everton archive. As one of life's observers, I particularly love black-and-white pictures; they're intriguing and I examine them closely.

Online and suitably hash-tagged, these monochrome mementos awaken memories from similarly nostalgic/thwarted Evertonians. They join the thread with their recollections of that match, their heroes and their recurring disappointments.

There's Roy Vernon in the tunnel at West Ham, wearing the white away kit, focussed and holding the match ball. Gordon West stands behind his right shoulder: we've heard so many stories about these old war horses, we feel as if we know them.

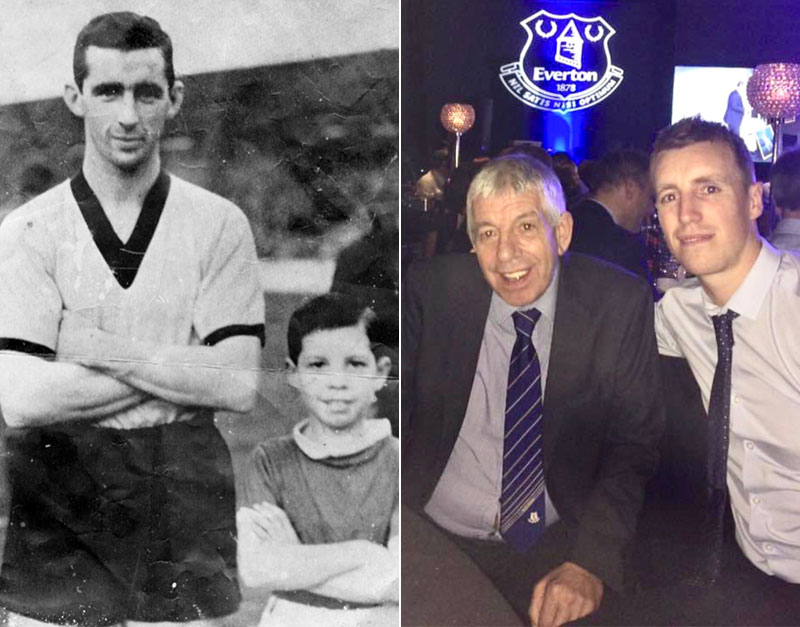

Vernon, the Everton captain was built like a whippet, the legendary taker of penalties (never, not even in training) and smoker of cigarettes (always, even in the shower) stands alongside a young lad with a beaming smile. I wonder what became of those youngsters, so fortunate to have been captured on film. How old would he be now? How did his life pan out? What does he remember about the day he got to walk onto the pitch alongside his heroes?

Some of the boys look overwhelmed and some are painfully shy but this one looked like it was the job he was born to do.

This is the story of Everton's first ‘boy mascot', John Murray.

Now based in Bristol, the only thing that's changed is the colour of his hair.

He still has a smile as wide as the Mersey and follows the Blues with as much passion as he did in 1963.

From a Royal Blue dynasty, 10-year-old John was in the Boys' Pen most home games. Occasionally, he would clamber over the top and crowd surf down the Gwladys Street End to join his Dad and uncles and watch the game from there. Some weeks there would be 65 000 people shoe-horned into Goodison Park.

After the Big Freeze of 1963 when all matches were postponed due to unplayable pitches, Liverpool FC returned with their ‘boy mascot'. There was a Toffee Lady at Everton, but no boy in a replica kit. The Murray Brothers decided they would change that and hatched their plan.

A trip from their Norris Green home to Jack Sharp's amazing football emporium in town was scheduled and the following home game, John was resplendent in his full kit complete with Roy Vernon's number 10, hand-sewn onto the back.

Ten minutes before kick-off, he was passed down above the heads of the crowd and deposited over the hoardings and onto the pitch.

“My Dad had told me to make my way to the tunnel, which I did. I didn't feel shy or nervous, I just did what I was told. When I got there, the policeman asked if I was the mascot, I said yes and he told me to go downstairs to the dressing room and wait for the team. I was so excited, I was going to see my heroes close up. When Roy Vernon came out and saw me, he said, ‘Alright Lad,' and off we went.

“I ran out first on to the pitch and stood there as the referee tossed the coin. I collected all of those pennies and saved them in an envelope.

“We went to every game, home and away. It was a way of life. My Dad, his brothers and their mates went on the ale at the away games and the kids just sat around listening to them talking. If it was a London game we would leave really early on the Sunshine Coach from the East Lancs Road and if it was midweek, I'd miss a day at school because I was present and correct at all of the matches, proudly wearing my kit with number 10 on the back.

“Boy mascots were a brand new concept and not all the clubs had caught on, so I'd often be the only one on the pitch. It felt amazing to be part of it, especially as Everton were superb and on their way to winning the league.

Harry Catterick had a masterplan to take the title and he was busy piecing together his team. Backed by the financial might of John Moores, he headed back to Hillsborough where he enticed his blue-eyed boy, Tony Kay and lured Alex Scott from Rangers to join the Mersey Millionaires. They both arrived at Christmas time only to learn that the frozen pitches meant there would be a backlog of matches for months.

When the season resumed, Everton went the remainder of it, unbeaten and were within striking distance of winning the League; it was all down to a home game against Fulham.

“The result that afternoon would decide whether we won the League. The buzz around the ground was incredible. It was mid-May and a lovely day; bright and sunny. Roy Vernon told me that if they won, I was to make my way to the bottom of the steps and wait for him, he would come and get me and take me up to where the medals were handed out. He scored a hat trick that day.

“I never doubted him for a minute. When the game was finished, Roy ran over to me and lifted me high into the air. I still have the picture in a frame.

There's another famous photo of the lap of honour; over-coated policemen line the perimeter of the pitch, poised to wrestle any would-be pitch invaders to the ground. Roy Vernon and an incredibly-youthful Derek Temple are in front of the St End goal. Albert Dunlop is catching up with Alex Young who's applauding the crowd. Top prize for ‘pure euphoria' goes to Alex Parker: socks rolled down and a hand on his chest as he laughs out loud in sheer jubilation, while Brian Labone, Alex Scott and Tony Kay bask in the love from the crowd. Look again and in front of Brian Labone, you'll see young John Murray leading the Champions of England around Goodison Park.

You'll easily recognise him because he has a smile as wide as the Mersey.